There are very few companies, if any, that will publicly say they pursue mediocrity, or that they really don’t care about their customers or their products. That just doesn’t happen. The problem comes about when the customer says these things about a company. Comments from end users naturally have enormous influence on a company’s financial future. The challenge has always been, however, to identify excellence and to put in place the mechanisms to guarantee it.

Pursuing excellence is a natural instinct. Finding a way to do things better, to make life easier and to ensure safety and prosperity are at every person’s very core. This translates across to industry as well, with the added advantage that in any design, manufacturing and shipping process, there is usually a great deal of repetition, which allows for analysis and testing at scale.

The Post-War Growth in Industry and Knowledge

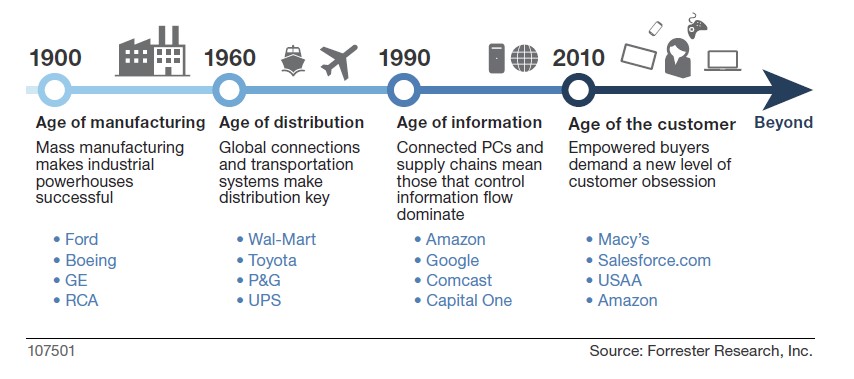

The past seventy years, following the logistical crises of two world wars, have presented a platform of measurable industrial growth on a global scale. Moving, as we have, from the age of manufacturing through the ages of distribution and information, to the current customer-focused era, we have been able to observe and test a range of processes to determine the best and most efficient way to get products to market and to get customers coming back.

Motorola, for example, was instrumental in developing the six-sigma model of pursuing excellence, primarily by manufacturing products in the hundreds of millions and being able to test using slight or wide variations with the goal of minimizing defects and maximizing profits.

I can suggest many other examples of large-scale excellence testing. The names are familiar to all of us: McDonald’s, Colruyt, Amazon, and so many others, that have been able to capitalize on their size to better understand the manufacture and delivery of their product.

Part of the challenge in creating a great product is knowing how to pair knowledge and experience. Very often, the theoretical understandings of how an activity should work fail to connect with the way that technicians perform this work on the factory floor. This can lead to defects, delay, and dissatisfaction between organizational layers.

As far back as 1999, an excellent study written by Anil Khurana and published in the MIT Sloan Management Review[1], pointed out that the management of complexity in the manufacturing process is dependent on management, engineers and factory workers consistently reinforcing and sharing their knowledge. New approaches to manufacture and assembly must be paired with workers’ ability and willingness to employ them. This helps offset what Khurana writes as a common reality in which knowledge of cause-and-effect relationships is limited.[2]”

New Technologies, Same Challenges

I have noticed the same challenge in the highly demanding world of software development, which has its own factory floor – rooms full of developers and testers, all intent of pursuing their own particular craft, often without full awareness of what the others are doing. Developers, for example, write code based on requirements given to them by the client or the business. Once the code, or pieces thereof have been written, the tradition has been to “throw it over the wall” to the testers who try to break it.

In an older age when software was boxed and shipped, there was a longer timeline between initial development and installation by the customer. But now, in the age of apps, there is a demand for much faster delivery of a flawless product. Hence, the industry has had to move from a sequential process called “waterfall” through a series of change in which silos or walls between experts have been forced to come down, and in which all players must learn more about what each other does. This is now called Agile Project Management or continuous testing.

As I wrote in a related article, Following the Lean S-Curve, there is a process required to get people to adopt and adapt. They have their own concerns about their jobs and security that sometimes override the deployment of best practices. But as Khurana writes, “Engineers and technicians need to possess a basic understanding of the process; they must know why rather than only how.[3]”

In the area of software development specifically, two books stand out as instructional on the management of change process in highly complex scenarios: the first is The Phoenix Project, which provides great insight into the management of any factory setting, from “raw materials in one side to finished goods out the other side, in a straight line.” The second is “The Kitty Hawk Venture,” which highlights the cultural changes and challenges that come with any attempt to generate renewed excellence using a combination of lean and innovative techniques.

Although Khurana’s MIT-Sloan article is old, having been published in 1999, I can suggest that it is timeless. These are the challenges that every company must face, and they must commit to doing so regularly and openly.

[1] Khurana, Anil (1999) Managing Complex Production Processes. MIT Sloan Management Review, Winter, 1999, Volume 40, No. 2. Retrieved from http://sloanreview.mit.edu

[2] Ibid

[3] Ibid, p. 89