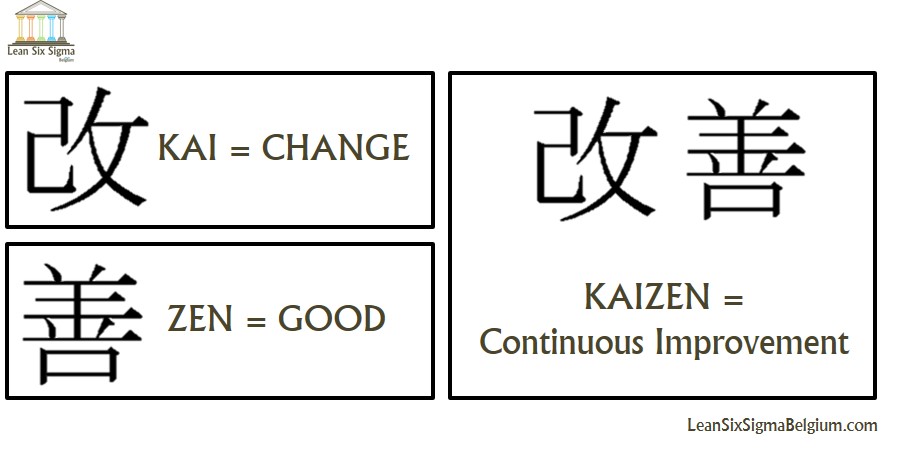

As a management concept, lean has several highly logical and practical disciplines, which at first glance tend to apply primarily to waste management, processes and data. I have written about these concepts before in articles such as Applying Lean and Excellence in an Age of Rapid Change and The Human Side of Continuous Improvement. It is important to remember that the body of wisdom that includes lean, kaizen (continuous improvement) and operational excellence still needs people to operate. Attributes such judgment, ethics, and engagement cannot spring from machines alone.

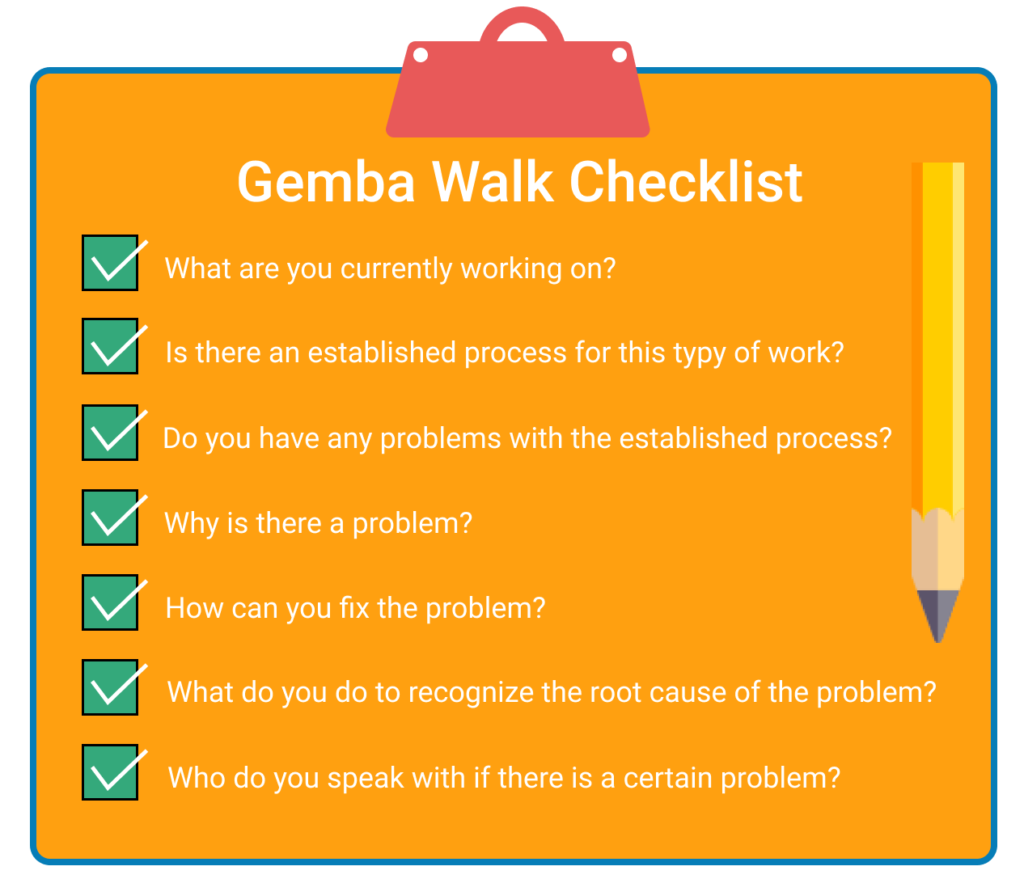

For example, certain segments inherent in these best practices can go overlooked. The gemba walk, for example, is the kaizen embodiment of “management by walking around” (MBWA), in which managers do get up from their desks to visit workers at their stations, to talk with them, to listen to them and to demonstrate that they understand them.

Related to this is the idea within kaizen that if an employee pulled the famous “Andon Cord” and brought a factory’s assembly line to a halt due to a perceived fault or defect, the manager is expected to not only walk over to the employee who pulled the cord, but also to thank him or her for doing so.

Such actions are worth thinking about over and over again. How many employees in any working environment would genuinely feel comfortable in pulling that cord, or demonstrating similar acts of empowerment without feeling enormous trepidation? How much commitment do managers show to individual acts of improvement? Do employees trust them not to issue reprisals? Is Management simply playing lip service to the idea of continuous improvement?

Could an Executive Ever Be Seen at a Personal Development workshop?

A case in point is the personal development workshop. Every day, millions of employees around the world attend classes intended to improve their skills and knowledge. How often does someone from management show up?

By being present even if just for a small portion of a class, perhaps the first few minutes, an executive does something that no teacher can do. He or she can bestow legitimacy and permission on the skills being taught, giving the employees greater confidence and willingness to perform the actions learned.

This has direct application at every level. For rote training where there is only one way to do a task correctly, such as operating a lathe or performing CPR, the presence of senior management can give employees a greater sense of connectedness and self-worth, which improves learning and retention.

In situations where an employee is learning a more esoteric skill – time management or conflict resolution, for example, the presence of senior management delivers permission for the employee to go ahead and make the changes necessary to ensure the new skills are fully leveraged.

The participation of senior management in every area where an employee pursues continuous improvement is vital.

A 2015 article from McKinsey & Company encapsulates this well. Entitled Bringing Out the Best in People, it matches lean principles to the essential efforts behind customer service and quality, a concept they refer to as Capability Building.

Capability Building

Capability building reflects the notion that work varies, especially in the services sector:

“The work itself tends to be highly variable—both in terms of content (such as the wide range of questions customers may have) and in form (such as the major swings in demand that may occur depending the time of day or year) … This compounded variability can make consistent delivery appear almost impossible, unless people can perceive the issues that are produced by variability, react to them, and provide solutions on a continuous basis.”

The paper’s authors add that capability building “involves more than just teaching people how to complete their day-to-day tasks. Instead, it focuses on a broader set of skills that increase each employee’s value to the organization, such as learning to reach problems’ root causes, or providing effective feedback.”

Such ideas are central to any established notion of customer service; however, they can be very difficult to implement. Some companies, especially young startups, benefit from a culture of informality and accessibility that has been there since day one. Startups share an energy and aggressiveness similar to that of young people in general, unencumbered by the weight and worries of middle age. Companies grow old and weighty, too, as the ranks of middle managers and administrators grow, as can be seen in the disruptors of just a few years ago, including Google, Facebook, and Apple.

Although some charismatic CEOs still exist, such as Virgin’s Richard Branson and Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, it becomes increasingly difficult for senior managers to make those gemba walks, and that difficulty is compounded at the middle management level. Stuck, as they are, in between the layers of the organization, “middle managers need to understand the enterprise-level picture, but they also must translate that understanding into the detailed, concrete actions that the front line is taking every day.”

The authors list four “must do’s” to achieve successful capability building:

- Engage every level of the organization

- Create excitement and pride

- Apply a range of learning techniques

- Institutionalize through HR

To make this happen, though, there needs to be a top-to-bottom culture shift toward the more human elements of lean, and although these cost little in terms of money, they will still prove expensive to deploy.